Economic futures for LLM inference

Inference providers will look for other lines of business.

None of this is investment advice.

Lots of talk these days about an AI bubble. It’s all a bit muddled, particularly because people refuse to define “AI” and “Bubble”.

I’ll try to be more concrete by riffing off the discussion of LLM inference economics.

Three challenges for AI inference companies

Serial monopoly in chip making

The only thing worse than buying from a monopoly is buying from a serial monopoly. A series of monopolists can charge markups at each step. For the foreseeable future, chip production will be a serial monopoly. This is a natural consequence of how challenging and specialized the industry is.

Not only that, but the software that fabs and chip designers use is an oligopoly. Many parts of the semiconductor supply chain are like this. Though TSMC exerts some monopsony power.

The end result is that inference providers have to give much of their profits to the serial monopoly. That inherently limits their returns.

Competition in model provision

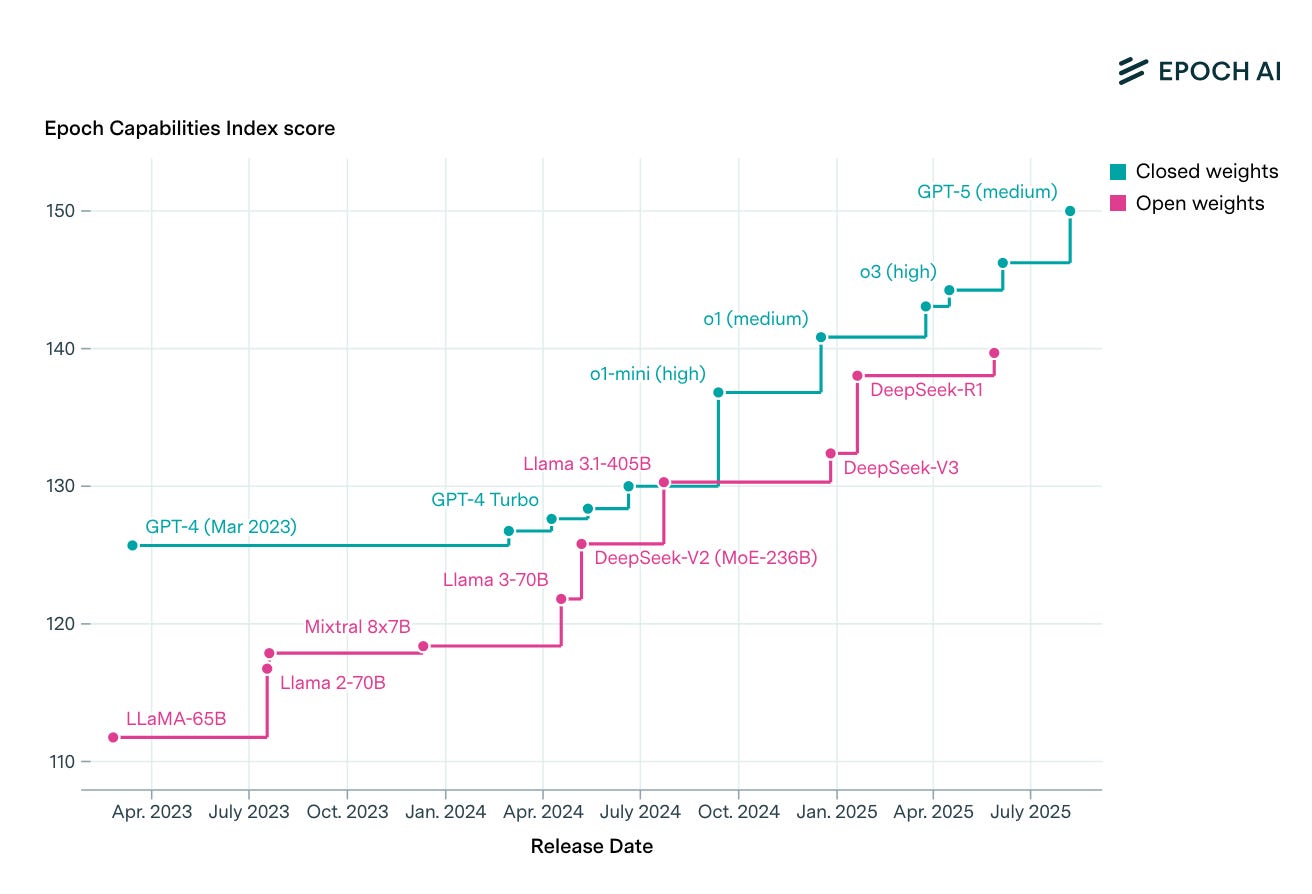

There are now roughly a dozen companies that can produce leading AI models. Over time, these models have become less differentiated and progress on real world tasks has slowed. The result is competition that brings profits close to zero just like we’ve seen with embeddings.

The elephant in the room is open-source models. They lag the benchmark performance of frontier models by roughly 3 months1. With open models, anybody with the money to assemble GPU’s (and the expertise to optimize their serving configuration) can now compete for inference demand. That opens up a lot of competition.

Technical risks

Buying hardware based on current AI models is a bet that AI inference will look similar in the future. If people discover how to do inference with less computation, that hardware spending is wasted. The clearest danger is small models. People keep figuring out how to pack similar performance into less memory. This is one reason why the trend towards larger models in the early 2020’s has stalled2.

New architectures might come out of this small model trend. While I don’t expect a new model to render GPU’s useless, a proliferation of tiny models might change the economics, leaving current players with sub-optimal hardware.

Even if AI inference stays roughly the same for the next 5 years, inference companies have to contend with model theft. The outputs of a model can be used as synthetic data to train a new model, which is hard to mitigate. Worse, the models are targets for theft by state actors.

Niches for AI inference

These challenges make it hard for inference companies to achieve the dominance enjoyed by other tech giants. They will continue to offer inference to the general public, just as today they offer embeddings despite low profits. But they will explore other options:

Inference oligopoly. Inference has gains from scale which produces winner-take-all dynamics. A few companies with the majority of inference demand can have low operating costs and monopoly profits. AI companies are pushing hard to be the next Google. We’ll see if that pans out, or if GPU scaling plateaus soon enough to admit many players3.

Enterprise AI. Economies of scale mean customers willing to buy inference in bulk can enjoy lower prices. Large companies may be willing to commit to one provider, particularly since it can offer employees a productivity boost. Additionally, the low-speed, low-cost inference achievable with large data centers and bulk purchases works well for asynchronous AI workers.

RL-as-a-Service. This is a buzzword I use to refer to the task of helping people apply AI to their idiosyncratic problems. The challenge of automating a task creates a moat, and I expect many different providers in this space.

Local AI devices. For people using AI assistants, response time matters. Brett Victor showed us the magic of responsive interfaces. Big data centers can’t help much with fast response time. In the limit you have your own powerful GPU running your AI assistant.

So what about the bubble?

Here’s a plausible path for AI companies:

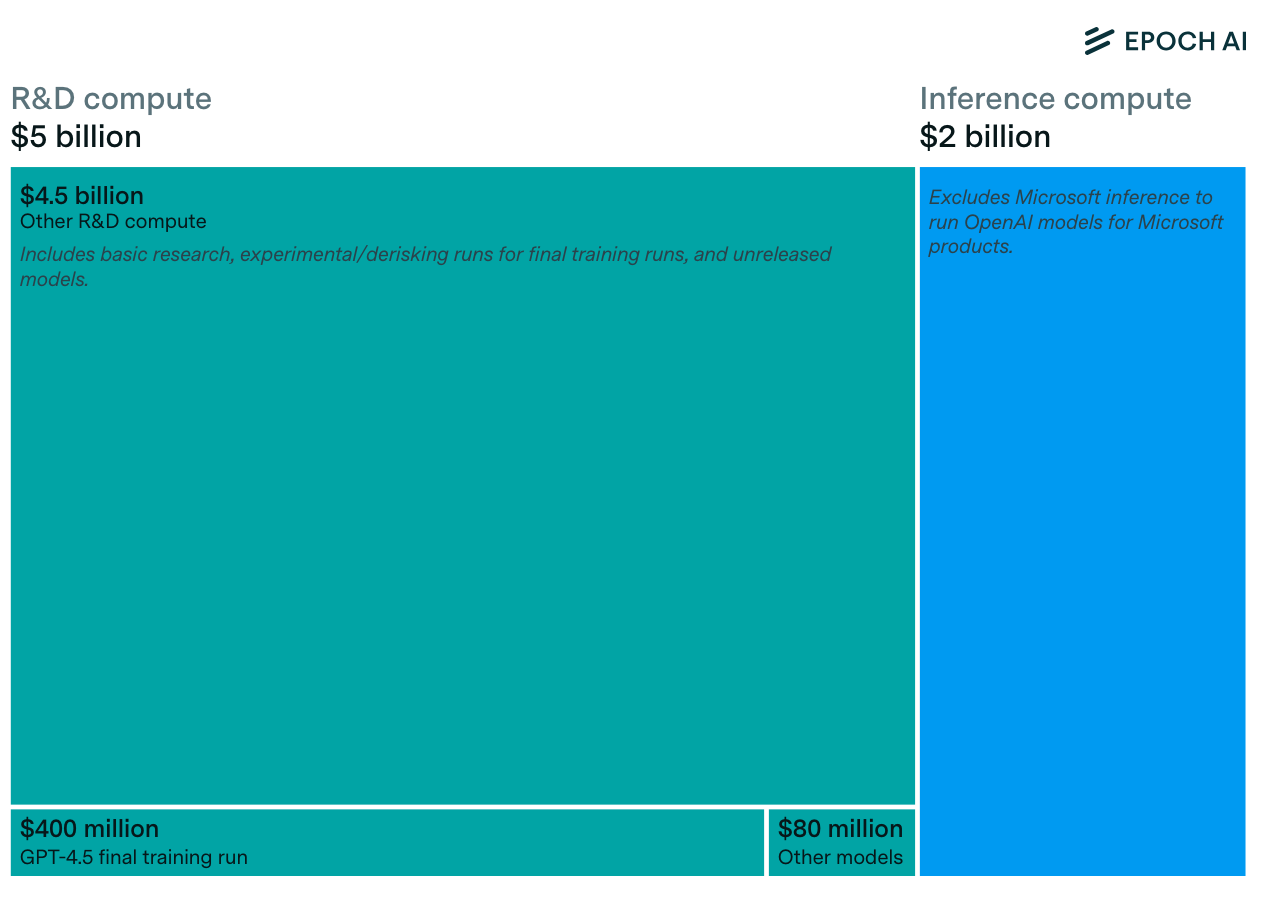

Big AI companies spend lots of money on hardware and R&D hoping to enjoy massive gains from scaling.

Scaling laws continue to hold. So training and R&D have disappointing returns.

AI companies cut training and R&D and pivot to doing inference and RLaaS.

GPU prices fall as companies sell the extra GPU’s they bought for training. Valuations fall if investors expected new sources of revenue from AGI. Though current P/E ratios look fine.

Without the moat from R&D and big training runs, everyone catches up to the frontier. Competition brings prices down to the marginal price and inference becomes ~100x cheaper.

Big AI companies stop trying to build AGI and look for other sources of profit.

So the end result isn’t doom for AI overall, just the end of billionaires trying to one-up each other with big training runs. Indeed, this path could lead to a proliferation of people building and serving AI models.

Despite the talk of an AI bubble fueling innovation, a crash would in fact be bad for AI progress. Like it or not, AI revenues are driving more research, better chip design, and new fabs. Not to mention the talent entering the field. A short term bust could set things back by a decade, and that would be bad.

It doesn’t have to be a bubble. Flagship AI models are already profitable. AI companies are safe if they scale hardware spend with inference demand. That means moderating spending on R&D and big training runs. And extending hardware depreciation schedules. They can also aggressively chase inference demand to get the benefits of scale in their data centers.

The path I laid out is already happening. AI companies have quietly saturated the scaling modalities while publicly hyping up scaling. Privately, I suspect they are coming around to RLaaS. Anthropic’s heavy focus on code generation is the beginning of this trend.

Appendix

Other things that help big AI players:

Buying up AI researchers to keep results private.

AI regulation (keeps out small players).

Government subsidies.

Low interest rates.

Reliance on large models, which have more returns to scale.

Making the stages of chip production more competitive OR combining the serial monopoly into a single monopoly.

Protecting Taiwan from a Chinese invasion.

Maintaining Taiwanese monopoly in leading-edge chip production as a payment to prevent alignment with China and as a means of committing to Taiwan’s protection.

Though I think the true gap is more like 6-8 months. Many open-source models seem to hill-climb more to get better benchmark numbers. These models also seem more finicky, when other inference providers run them on a new configuration, benchmark scores are lower. Outside of benchmarks, OS models can be less practical.

Regardless, these models are still very capable, they just lag the frontier more than you might expect from benchmarks.

Of course it’s possible for a larger model to have enough capability to overcome the challenges of serving it. In other words, the intelligence per unit cost could be higher for larger models. But that doesn’t seem to be the case at the moment.

Another factor is the demand for more capable models. Are people willing to pay more for better models? So far prices have stayed the same as models have gotten better, but companies are prioritizing user growth rather than maximizing profits so we will have to wait and see.

For example, there are limits to how much you can scale the batch size because eventually the KV cache takes up all of the high-bandwidth memory (see fig. 15 here). This gets worse if users need long context or you employ lots of chain-of-thought. The question becomes whether new generations of AI hardware can cost-effectively increase the amount of high-bandwidth memory in their racks.

To be fair, this isn’t the only return to scale in AI datacenters. Techniques like expert parallelism will still exist.

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot; your breakdown of the serial monopoly and open-source models' impact on inference economics is so smart and realy insightful.

The serial monopoly framing really clarifies why inference margins are under such presure. Its interesting how you point out that open source models lagging by 6-8 months might actully be the bigger competitive threat than the benchmark numbers suggest. I wonder if the pivot to RLaaS happens faster than most expect, especially if scaling plateaus become more obvious in the next year or two.