Breakthroughs rare and decreasing

Innovation is trying stuff. Eventually you find something good enough.

Fellow optimists seem to hold some strange views on how innovation works. This has become apparent when people talk about AI as something that will cure cancer by thinking about it, or derive all of fundamental physics by watching an apple fall.

Statements like these are silly, I want to address some ideas about innovation that might be at the root.

Innovation is mostly trying stuff

The way I think about innovation is Trying Stuff. The best way to determine if something works is to try it in the real world. Most innovation comes from trying different things in a particular domain and keeping what works. Everything else is secondary. Fancy theories make trying stuff more efficient, but aren’t required for trying stuff to work. Standardization and automation are valuable because they accelerate the process of trying stuff.

Most major discoveries were made by people trying stuff, with theory and standardization happening later. Steam engines were in use before thermodynamics, many drugs were discovered on accident, and the green revolution happened because of systematic tinkering.

The implication is that brilliant theory can only get you so far. You need to actually collect data and try things out to make a discovery. The trying things out part is the bottleneck in the process. You have to physically move atoms around and wait for the results. A data center full of Nobel Laureates would spend most of their time waiting for results, not making discoveries1.

Eventually, trying more stuff is useless

Trying stuff comes at a cost. There is the physical cost of doing the experiments and the opportunity cost that you could have done experiments in some other domain. Combine with diminishing returns and eventually it doesn’t make sense to continue experimenting.

This is stronger than the idea of “low hanging fruit”. Not only do the easy opportunities get found, it stops being useful to even look for new opportunities in a particular area. The marginal benefit is too small.

Most domains see an end of history

At the end of my series on solving climate change I noted:

After looking at the future of cleantech, it feels like we’re nearing an equilibrium. The end of the century may see the end of terrestrial engineering. We found cheap energy sources that won’t be usurped in the forseeable future. The quirks of renewables will propagate into our production processes. After that, what’s left to change?

This is true of all technology. We find an effective way to do something, tweak it a bit, and then kind of stop2. This is an odd sentiment in an era defined by ever improving computers, but look outside the enchippening and you’ll see it’s true.

Food products like bread, cheese, meat, beer, and wine are made with techniques that would be recognizable to people centuries ago. Indeed, rain-fed agriculture still provides virtually all of our food, as it has for millennia. It looks unlikely that vertical farming will change that. Of course, we have substantial automation in agriculture, but that’s because we didn’t find an alternative to growing crops. We found new ways to increase yield outside of the growing process.

Even semiconductor fabrication and AI scaling follow the same pattern. We scale up an idea until it reaches physical limits then innovate elsewhere. Smooth progress comes from stacking hundreds of S-curves.

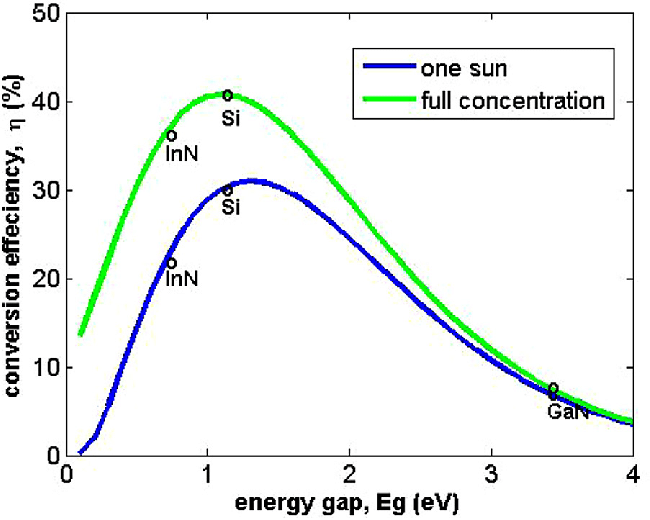

After many S-curves, progress slows. Haber-Bosch is how we produce fertilizer today and I’ve realized we aren’t going to find anything better for the foreseeable future. It takes iron and air and makes bread for gods sake. Or consider that silicon, the second most abundant element in Earth’s crust, has a bandgap that makes it perfect for absorbing the sun’s emission spectrum in solar panels. Need we search further?

Look around at everyday objects and this insight becomes trivial. Things like cups and chairs and pens are already optimized. There is little need for further cup research. There is no magic recipe for making cups more efficiently. Our world is grounded in physics and it’s unlikely we’ll find a substantially better production process.

So innovation jumps around. We encounter a new problem, fiddle around, find a good solution and then move on. Everything converges as we figure out the right way to do things. Unless our circumstances or way of life changes, we should expect society to crystallize around specific technologies and production processes.

That said, there’s still so much room for improvement. The world that we’re converging towards is wildly different from our own. But if we’re going to build a better world, we need a realistic understanding of how innovation works and what is possible.

Except in math.

The key barrier to further development is often economics. We have found many different ways to make titanium for example, but they simply aren’t competitive with the current system. This is true of many beautiful ideas for how to do things differently.

I broadly agree with this, but I think there are phase transitions that will accelerate the rate of technological growth, like true "Einstein's in a data center" and/or whole brain emulation (e.g. see Robin Hanson's argument on the latter).

> Indeed, rain-fed agriculture still provides virtually all of our food, as it has for millennia. It looks unlikely that vertical farming will change that.

I feel like we have discovered the real upgrade for this (CO2 electrolysis using solar or fusion electricity, some biochemical path to higher-order hydrocarbons and ultimately precision fermentation/cellular agriculture to make foods), but the required technology is far away from becoming cost competitive.