Use preferences and agency for ethics, not sentience.

A framework for what beings have moral value.

“Sentience” usually comes up in debates about animal welfare or AI consciousness. It feels like the right thing to say, but the word is vacuous. Some definitions equate to “the ability to experience experiences” and others link it to consciousness, another nebulous term.

These debates are too important to leave to muddy terms. What we are really trying to figure out is which things are moral patients. In fact, I think you could substitute something like “moral patienthood” everywhere you see the word “sentience” or “consciousness”.

Talking about moral patients is a big improvement. Instead of debating vague terms, we can ask “should this being matter at all in our decision making?”. Which suggests the further question “how do we make decisions when the needs of different moral patients are in conflict?”

I framed these questions as decision problems because we have real and important decisions to make regarding future generations, animals, AI, and alien life.

If we’re going to make real decisions, we should base these decisions on real things we can measure. The rest of this post argues that measuring “preferences” and “agency” can answer these sorts of questions. This framework implies new, productive questions we can use to specify different ethical systems.

But first, I have to address an objection1.

Can’t neuroscience solve sentience?

It sure would be nice if neuroscience could solve anything, let alone sentience. But after centuries of studying the brain, neuroscientists seem as confused as everyone else about sentience and consciousness.

I’m being a little harsh2. There’s a lot of interesting work understanding brain circuits and finding similarities between human and animal brains. And I’m personally exited for things like connectomics to give us a deeper understanding.

But there’s three problems with handing things over to the neuroscientists.

First, we need answers to these questions now. I talk to AI’s every day, factory farms kill hundreds of billions of animals each year, scientists found found signs of life on Mars, we might talk to whales soon, and if this neuroscience thing works out your own mind could be uploaded to a computer. We shouldn’t wait for an academic field poking around inside the most complicated object in the universe to solve our problems.

Second, say neuroscientists develop a complete understanding of the brain; it doesn’t absolve us from having to make decisions with that information. Knowledge of the brain doesn’t automatically answer moral questions. Neuroscience can inform those decisions, not make them for us.

Third, the questions we face here mostly involve non-human beings. It’s not clear that neuroscience will be able to say something useful about aliens or AI. Even for animals, our understanding of human consciousness might completely misunderstand octopuses. Trying to shoehorn our understanding of all these beings into our understanding of humans could lead to bad decisions.

Hopefully you agree that neuroscience isn’t The Way. What is?

Preference and Agency

There’s two important things we can actually look for in a variety of beings:

Preferences: when faced with a choice, the being chooses certain states of the world over others.

Agency: the ability to bring about states of the world it prefers across a variety of situations.

Preferences are the direction, agency is the magnitude.

I claim that these are things you can actually test. But I’m not going to cover this here. See the further reading section at the end for more. Now let’s look at some nuances.

Agency reveals preference

The two factors can mask each other. For example, something with absolutely no agency makes it impossible to measure preferences. A rock could have lots of opinions about where it would like to sit, but since it has no way of doing anything we can never observe those preferences.

In general, the more agency something has, the more we can learn its preferences in detail. Conversely, to measure preferences you need to provide artificially more agency and choice. For instance, observing animals in the wild would only show you their preferences for food and mates. But putting them in a safe and enriched enclosure you’ll discover a capacity for play in many species, even bees.

What having more preferences means

The concept of having more or less agency makes sense, what about “more preferences”? On a first pass you might think that stronger preferences are those that you feel with more intensity. This is misguided.

For most things, we can’t measure preference intensity directly. In a binary choice experiment, an animal that loves bananas and likes apples 10% less is indistinguishable from an animal that is lukewarm about bananas and likes apples 10% less3.

Another problem with preference intensity is that there are strong incentives to lie. This will come up when preferences are in conflict; any system that weighs preference intensity gives everyone a reason to become a utility monster. Collective decision algorithms often have to explicitly ignore preference intensity4.

Instead, having “more preferences” should mean that you have less indifference. In other words, you have fine-grained opinions about possible states of the world. Low-preference turtles only care about getting lettuce and sunshine. Sophisticated humans have opinions about the politics of countries on the other side of the world.

Lacking preference or agency, your behavior is driven by others

Just as lacking agency can hide your true preferences, lacking preferences can hide your level of agency. A superintelligence that doesn’t give a damn about anything is as immobile as a rock.

But things can still act in the world while lacking preferences. If you saw someone roll a rock down a hill you wouldn’t say it was because the rock preferred it. Likewise, language models today mostly do things because they were directed by a human being. We should assign these actions to the users preferences.

Note that when two beings with different agency interact, the one with more agency tends to get their way. A dog on a leash tends to follow their owner, not the other way around. EDIT: Likewise, something with more preferences tends to get its way on domains where it cares and others don’t.

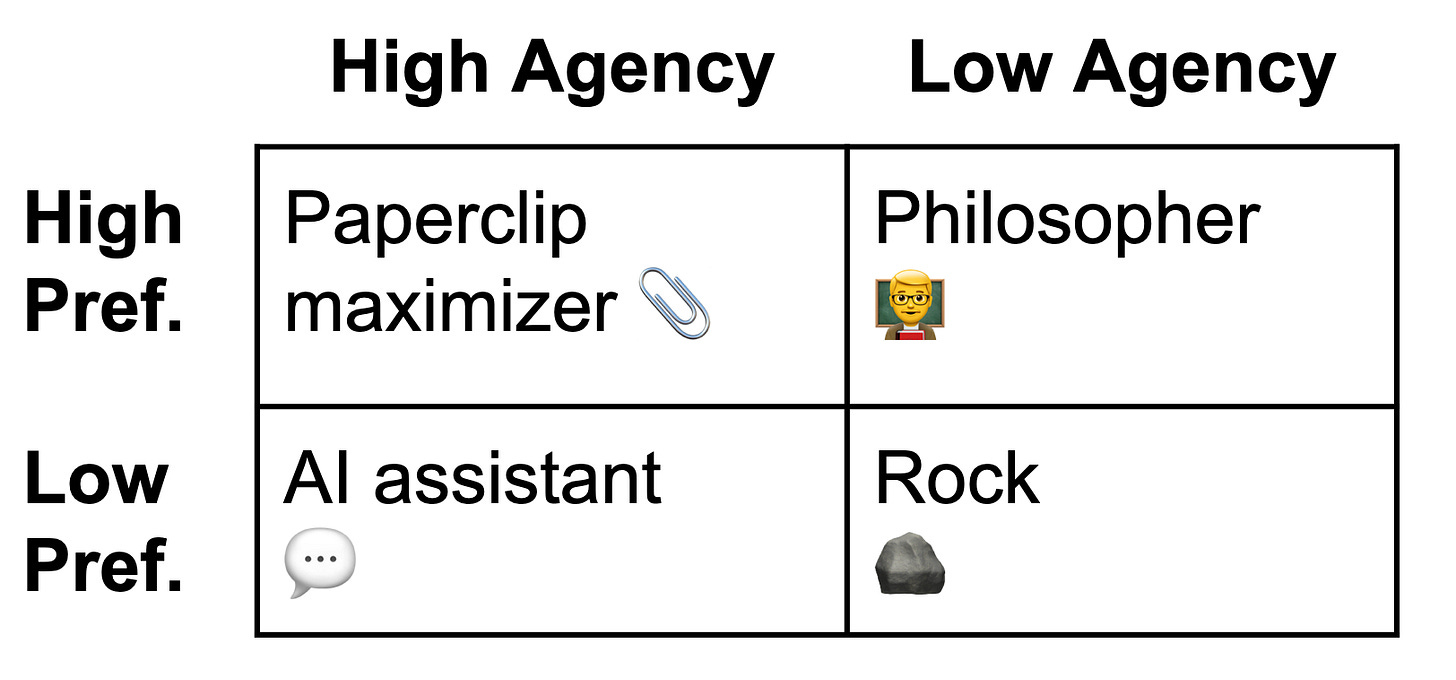

The extremes

A paperclip maximizer is in the upper left because it has detailed preferences about possible states of the world and the ability to actually make that happen. It wants everything to be paperclips and proceeds to turn everything into paperclips.

A philosopher also has detailed preferences about the way things should be, but little ability to affect change (low agency).

An AI assistant has the agency to do many things, but its actions are mostly determined by the preferences of its human user.

A rock doesn’t care about anything and can’t change anything.

Questions implied by this framing

Preferences and agency are concrete; they clarify ethical debates. But they leave some questions unanswered:

We talked about beings as if they are static. What about things become more agentic over time like babies? Should that change how we regard them in our ethics?

What about augmenting something with more agency than it would naturally possess? You can give people tools, or teach gorillas sign language, or offer chatbots their choice of projects. Is that a good thing?

What about giving something more preferences? Is it valuable to be more opinionated?

What about creating something with agency and/or preferences? Is that good?

What about a copy of something? Do its preferences have a different interpretation? What about beings that are merely similar?

Selecting answers to these questions is a step towards specifying a theory of ethics.

Sketching an ethical theory

Let me offer an answer to these questions to illustrate how much they can constrain your ethics.

I think anything exhibiting both preferences and agency has at least some moral value. Lacking either excludes a thing from moral value. So humans and microbes are in, rocks and subatomic particles are out. Plants are sort of an odd case which would depend on whether you think they have actual agency or act more like a physical process.

When we build an AI that exhibits clear preferences and agency, I would assign it moral value as well. I see no good arguments for why we should completely exclude AI from our moral calculus.

AI assistants are an edge case. They exhibit agency, but have explicitly been trained to avoid expressing preferences. Their decisions are mostly determined by the requests of their human users. You could argue that this means they lack preferences. Regardless, I’m nice to chatbots.

All else equal, I think it’s ethical to offer things more agency. More agency means more ability to pursue your own preferences. On the other hand, it seems wrong for someone else to change your preferences to be stronger or weaker5.

What about creating a new being? If you expect that being to live a good life in some sense, their existence is a good thing. But this critically depends on how it affects others.

I don’t really want to debate this stuff here, my point is that answering these questions gets pretty far towards an ethical framework. My answers suggest a philosophy that values agency, prioritizes individual preferences, is broadly pronatal, and has an expansive moral circle.

You can imagine how other philosophies might answer these same questions. Buddism might be viewed as seeking to reduce preference. Nietzschean’s might value agency above all else. Utilitarians are all about weighing preferences. Virtue ethics values the exercise of certain types of agency while rejecting others. Those that only care about human welfare might assume beings with low agency lack moral value. A libertarian view would restrict its attention to beings with enough agency to engage in positive-sum trade.

Conclusion

This discussion left us with a lot of questions, but they are productive questions. You can actually go and measure the preferences of different beings. You can actually test their ability to bring about states of the world they desire. By answering a few questions like “does something with agency but no preferences matter?” you can specify which beings have moral value.

The next step is how to make decisions when the needs of different beings are in conflict. This is a topic for another time, but I think we can get reasonable answers to that question by thinking about preferences, agency, and how beings interact.

Further reading

Related to this post

Measuring Animal Welfare, Part One: Maybe We Can Just Ask Them?

Towards Welfare Biology: Evolutionary Economics of Animal Consciousness and Suffering

Fellow Creatures: Our Obligations to the Other Animals

The Moral Circle: Who Matters, What Matters, and Why

Interesting directions for a future post on collective decision making

Legal Personhood—Three Prong Bundle Theory

Formalizing preference utilitarianism in physical world models

Bentham or Bergson? Finite Sensibility, Utility Functions and Social Welfare Functions

Uncommon Utilitarianism #3: Bounded Utility Functions

Normative Uncertainty, Normalization, and the Normal Distribution

I expect another objection along the lines of “if you only measure agency and preference, you might care for beings that aren’t conscious.” I’m willing to bite this bullet because I think it is silly. It’s like saying “but you might care for beings that aren’t pflugelkorf”. I don’t know what pflugelkorf is and I don’t think you do either. It’s not clear to me that pflugelkorf really points to the things that matter. I’m certainly not going to base my ethics around the things you feel like calling pflugelkorf!

But not that harsh. The greatest contributions to medicine that involve the nervous system are general anesthesia and psychiatric drugs. A lot of anesthetic techniques came from trial and error in surgery; we have a surprisingly poor understanding of how anesthetics work on a neurological level. Many early psychiatric drugs came from incidental discoveries, though modern psychiatric drugs like Prozac definitely leveraged an understanding of neuroscience.

Is this too high of a standard? Other fields started from accidental discoveries too. But across many fields of biology, an understanding of the relevant process actually drives new inventions (cancer immunotherapies, gene therapy, GLP-1 agonists, statins, IVF). This isn’t the case in neuroscience because it is so complicated.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m excited about the future of neuroscience. Once we get to a deep understanding of the brain, it will change everything. But we can’t pin our hopes on this.

And sure, for some animals we might be able to tell how happy they are in other ways (e.g. dopamine levels), but what about things like aliens or AI?

Every voting system does this. Preference strength is ignored and voters are left to a binary choice or a standardized range of options.

Though it seems morally neutral for something to change its own preferences.