My uncle is anxious about flying, before getting on a plane, he usually needs a stiff drink or two to calm his nerves. I suspect he’s not the only one, airport bars are pretty popular despite the ridiculous prices.

But the main reason these bars are packed is because air travel is hell.

I flew across the U.S. recently, and I was struck by how much time is wasted. Sitting in traffic, checking luggage, security, sitting at the gate, loading the plane, and taxiing for takeoff, all with a matching set of time-sinks at your destination. And that’s for a typical experience; delays, missed connections, or overbooked flights are all too common. Taken together, air travel can waste an entire day even for relatively short flights.

By some coincidence, I re-watched Catch Me If You Can a couple days after the trip and was shocked by their depiction of boarding a plane in the 70’s. You could just … walk right in.

Of course this is an exaggeration1, but it provides vision for what travel could be: passengers get dropped off at the airport and walk unhindered onto their flight, with the door-to-seat time measured in minutes, not hours.

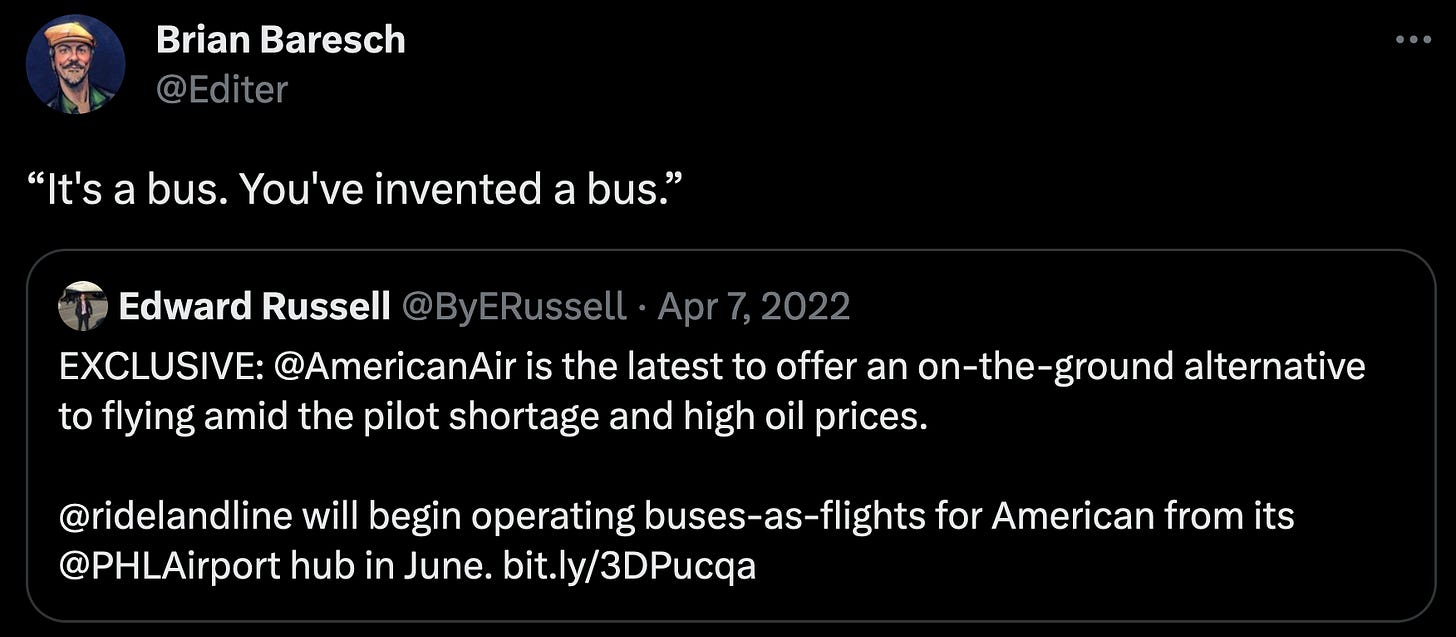

It would almost be like … riding a bus.

I think this vision is possible. I think we can make air travel faster, cheaper, and more comfortable, and that we should use all the innovations at our disposal to get there.

We’re too comfortable with the idea that flying is precious, reserved for exotic vacations and big conferences. But there’s no reason we can’t use technology and policy to make flying as convenient as getting on a train. I dream of a future where flying is so abundant that people take a plane to work everyday. It should be so effortless and mundane that nobody needs a drink to make travel tolerable.

Let’s look at a few unorthodox ideas that could making flying much better.

Remove Luggage and Redesign the Interior

This is probably my most controversial point: airports shouldn’t have any luggage2. Passengers should be limited to bringing a single backpack on the plane.

The thing is, we already have a system for moving heavy boxes around the world; its called shipping, and its fast, cheap, and better for the environment. Flights are expensive, and every bit of takeoff mass should be for moving people, not stuff we can put on a truck. With a little planning, consumers can ship their luggage ahead of time to their destination34.

It’s one thing for a single passenger to ship their luggage overland, but when removing luggage from airports becomes a collective choice, it radically changes the design of airports and airplanes.

Most obviously, with nothing to drag around, everyone can get around the airport faster.

But we’ll see bigger benefits in airport security. If people were limited to one small bag, security could scan them very quickly. Additionally, we can do away with the huge amount of effort that goes into inspecting checked bags.

We get dozens of logistical benefits by taking luggage out of the equation. Airports could remove the staff and infrastructure required for moving checked bags and use fewer security checkpoints since each one will have higher throughput. Airports become smaller and easier to run.

It can be hard to quantify all of the benefits, so let’s focus how this would change the flight itself. Let’s assume we’re on a 737-8005: the payload mass is 24,000 kg and the average passenger weighs 80 kg (75 kg + 5 kg backpack), so we could accommodate 300 passengers. This is over 60% more than the maximum 189 passengers on a flight with luggage. The real value will be lower due to engineering tolerances and the weight of the new seats, but it may be possible to cut ticket prices in half.

Even if we don’t fill up the plane, a little extra space can make the flight much more comfortable. A lot of new options open up when we lose baggage. Double decker seating? Bunk beds? Cocktail lounges? The sky’s the limit. Adding beds is particularly interesting, since sleeping reduces the net time cost of a flight. If passengers can sleep comfortably, we’ll need a new name for the red-eye.

Hopefully by now you’re an anti-luggage radical, but how do we make this happen?

We’re stuck in an equilibrium where planes are made with a luggage compartment, consumers expect to put their luggage under the plane, and security is designed for passengers with multiple carry-on bags. Since passengers get the same prices and treatment regardless of the number of bags they have, there’s no advantage for people who pack light.

The first step would be to offer an accelerated security line for passengers with only one small bag. A scanning machine could specialize in small bags so that people don’t need to take anything out. Carriers can also offer cheaper tickets to passengers that don’t bring luggage.

Next, regulatory agencies and airlines could explore removing the luggage compartment entirely to see how much seating could be increased and assess consumer demand. Then carriers can offer separate flights for travelers who only bring a backpack. With a redesigned airplane and streamlined security, travel can be faster, cheaper, and more comfortable.

Build Small Airports with Small Planes

Flight loading time goes up with the number of people6 which means that smaller flights can save time. But modern airports are built for large airplanes and long flights. Even if a passenger saved loading time, they would still have all the hassle of going to a huge transport hub.

Rather than try to adapt small, efficient flights to existing airports, a second air network should be built. Imagine a tiny airport in most major towns with no traffic, no lines, and small planes able to take you to the closest hub.

This would vastly increase airplane use for most people. Rather than drive to work, why not take a short hop to any city within 200 miles? You can even work while you’re in the air. For regional trips, passengers can string together a few local flights instead of driving while international travelers can take a short hop to a central hub and skip driving, parking, baggage check, and security at a busy airport.

This gets us much closer to the vision of airplanes-as-busses than trying to scale big flights further. I estimate it would take 300 such airports to be able to reach any point in the continental U.S.7.

But what kind of plane is small enough and cheap enough for this new network?

eVTOL’s are a perfect fit. With vertical takeoff, they don’t need a large runway, so airports are much smaller and easier to build. And since they’re quieter, they won’t create noise complaints. The lack of fuel, smaller size, and lower speed also make them less of a security risk. They’re safer too, there’s little risk of a crash landing when you can land anywhere.

The main issue with eVTOL’s is range and price. We would need a range of roughly 200 miles using energy-dense batteries with a long life. The Lilium jet is aiming for 190 miles of range, but at a high price. I’m optimistic that innovation in structural batteries, electric motors, and airplane materials can produce eVTOL planes that make this network feasible8.

What regulatory environment is needed for this new network? Applying the same regulation used for jumbo jets could kill the industry. The FAA is working hard to keep up with new developments in aviation, and I hope they keep open the possibility of using small electric craft for short trips.

Invite Competition at Every Level

Deregulation efforts in the 90’s succeeded in lowering prices and increasing quality through higher competition. But the reforms fell short in many ways. We need to think about how we can encourage more innovation in air travel.

Existing regulations have resulted in a limited number of airlines operating in America. Places like Europe have many more carriers and lower costs. Lowering barriers to entry and permitting more carriers in the U.S. is a good first step.

Next, airport gates and takeoff slots can be allocated better by applying economic principles. Access can be auctioned the same way we allocate broadband spectrum, with a fee structure designed to encourage carriers to use their slots effectively9. If an airline can’t use all of the slots they buy, they should be able to sell or sublet them to other carriers.

More innovation in airport design will come about if more airports share the same metropolitan area. This is another benefit of an eVTOL network, people can hop to the best-run transit hub within 200 miles instead of being stuck with the one nearby.

I you’ve ever used Google Flights, you have an intuitive sense of how complicated booking can be. The amount of effort that goes into flight pricing and routing begs the question of whether a common marketplace should be built. Booking has all the hallmarks of a combinatorial auction, where search costs and a lack of information create inefficiency. Research into government-supported marketplaces for flight booking could have a huge payoff for consumers.

And let’s go back to those airport bars, why are the prices so high? Well, all the shops in the airport have limited competition, high fixed costs due to security rules, and a captive audience. With no luggage and streamlined security checks, all of those businesses can move outside the airport, where passengers can flit between what is essentially a shopping mall and their gate. This increases competition and removes the security restrictions, which should lower prices and increase quality.

Airport food is overpriced, but in-flight markups are even higher. While in the air, carriers have a monopoly on every product, from food to Wi-Fi. To fix this, the law could require that airlines allow several competitors to provide food and entertainment in-flight10.

The creative destruction of competitive markets can produce surprising results. When given the opportunity, innovators can revolutionize the flight experience.

Remove Staff and Increase the Supply of Pilot-Hours

Staff makes up a third of a flight’s cost with at least 2 pilots and 4 crew members required by law on every 737 flight. Cost disease means that staff pay will only increase, so automation is critical to keeping prices down.

Let’s look at crew members. Flight attendants play many roles in food service, customer support, and emergency medical services; some of these roles will not be easy to replace. However, food and beverage service is ripe for innovation. For instance, imagine a little conveyor belt rolling food down the aisle, a robotic dolly, or some sort of vending machine serving customers. With streamlined payment systems and robotics, there’s no need for flight attendants to personally hand out food multiple times a flight.

You may argue that if this was such an easy win, airlines would have done it already. But passenger air travel is heavily regulated, I doubt some new food service contraption would be allowed. Regulatory agencies, consumer advocacy groups, and carriers will have to work together to find solutions that reduce costs without harming accessibility or safety.

The other roles that flight attendants play should be un-bundled. Each flight could have a single customer support member and one medical professional. Alternatively, airlines could ensure there are people with medical training on every flight by subsidizing their tickets.

Pilots are even more expensive than flight attendants because we can’t fly without them. Or could we? I was surprised to learn that while almost all takeoffs are done manually, autopilot is often used in flight and during landing, especially in difficult conditions. That makes me wonder: do we need a second pilot in the cockpit?

Military drone technology has shown us that its possible to control an aircraft from the other side of the world, why not have a dedicated co-pilot on the ground ready to step in if the pilot is incapacitated? If the copilot is often not needed, why not have them monitor multiple flights at the same time? Its easy to ensure that your copilot is always fresh by swapping in a new one every few hours11.

Starting with this remote copilot system, we can slowly move to a system where most flights are autonomous12. A pilot on the ground would perform takeoff and landing while a copilot closely monitors many flights simultaneously. This would dramatically increase the supply of pilots, since they only really need to focus on the first and last 30 minutes of the flight.

But we can go further by increasing the total supply of pilots. The number of pilots is limited by strict training regulations and a professional licensing organization formed to keep wages high. People who study the airline industry agree that these requirements can be relaxed without compromising safety.

Another option is to allow the use of nootropics to increase the amount of time a single pilot can safely operate. The FAA could to allow pilots to use drugs like Modafinil to improve flight performance and increase total hours13. A flight simulator study of pilot performance on different stimulants is a good first step towards considering their use on the plane.

By relaxing crew member regulations and switching to a remote copilot, we can at least halve crew costs, reducing ticket prices by 15%.

It’s unclear whether these steps will reduce the employment of pilots and crew given the increase in flights and number of passengers. But, disruption of people’s livelihood is usually a regrettable consequence of progress, and Trade Adjustment Assistance could help ease the transition. Pilots will move to a role monitoring many flights simultaneously while crew will move to the more numerous, smaller flights on eVTOL’s.

Conclusion

I’m making the classic mistake of questioning people on-the-ground working to make air travel better, and I expect I’m wrong in a lot of places. But air transit deserves some new thinking. Our current equilibrium came about due to a tug-of-war between regulators, companies, and consumers, it’s not clear that it’s ideal for everyone.

Unfortunately, the airline industry moves slow, the service lifetime of a 747 is 25 years, so changes to airplane design will have to wait roughly that long. Many good ideas for reform will take decades to be realized. Even big improvements will face strong headwinds from consumers, companies, and regulators accustomed to the status quo.

But there are some concrete steps that can be taken in the meantime. Replacing crew with automated food service, training more pilots, and studying seating arrangements without luggage are a good start. These changes alone may be sufficient to halve ticket costs.

But the most radical change would be the construction of an eVTOL network independent of normal airports. Unlike the other tricks I’ve mentioned, this has the opportunity to make air travel a part of daily life. While passengers will still need to get on a large plane for long trips, this short hop network could replace a lot of domestic flights and ground travel.

This would usher in a world where taking flight is a daily experience, not a luxury. I expect this will reshape society akin to the invention of cars; it will expand everyone’s horizon in terms of the places they can work and play. And that horizon will be filled with people reaching farther than they ever could.

Appendix: Technological Improvements to Make Travel Greener, Faster, Safer, and More Pleasant

I don’t know if you noticed, but there have been a lot of technological developments since the 747 was introduced in 1970. We should at least consider whether quantum-AI-blockchains can improve our situation. Some ideas:

Making synthetic fuels from the CO2 in the air is starting to look promising. Not only would this make air travel carbon-neutral, but fuel costs make up 15% of flight costs, so a cheap, high-quality alternative with lower price volatility would be a big deal.

The case for small-scale stratospheric aerosol injection is starting to look compelling. Could we modify commercial flights to release SO2 to test the technology and cool the planet?

We should experiment with new forms of air travel. Rockets, supersonic planes, scramjets, airships, flying cars, eVTOL, and methalox engines should all be given serious consideration.

Fill and flush deplaning can move people in and out quickly, saving a lot of time.

Facial recognition can eliminate the need for tickets. Facial recognition is already being used at several airports, so why not use it to our advantage? Tickets you buy can be linked to your face scan, so that you can just walk through security and onto your flight without being stopped. Ideally we would find a way to do this in a privacy-preserving manner eventually.

I can’t find the original source, but I’ve seen someone suggest time-locking the cockpit for the duration of the flight to prevent hijacking. This is similar to how bank safes and pharmacies discourage theft today.

Airports are implicated in the spread of infectious disease. Far UV-C sanitation and nucleic acid observation at airports can slow pandemics and mitigate bioterror attacks.

Adding amenities like larger screens, Wi-Fi, cell coverage, VR headsets, and game consoles can increase a flight’s value for the price.

Passengers and their belongings can be weighed as a group with money back to families that pass under a total weight threshold, incentivizing people to pack lighter. With the whole family and their luggage on a platform, it’s also a good time to take a photo!

Blended wing bodies or truss-braced wings might provide more room per flight, increase fuel efficiency, and reduce noise.

Flying in formation can reduce fuel use of the trailing plane by up to 10%.

E-scooters in airports could move people quickly and cheaply to their terminal. This is another benefit of removing luggage.

Switching to methane or LNG fuel would be a paradigm shift for planes. LNG has higher energy per kg, half the emissions, and would produce less of a contrail. The lower volumetric density could be compensated by using a blended wing body and reclaiming some of the space taken by staff and luggage. New engines like Astro Mechanica’s electric turboprop could utilize the cryogenic methane to make the engines more efficient14.

Airlines make a profit from their frequent flier programs, not from selling tickets. Allowing airlines to use more sophisticated financial schemes with their frequent flier programs may lower prices further. Perhaps you could pay ahead to lock in a price for a flight you make regularly?

The Otto Celera 500L can offer better fuel economy for 6 passenger flights. Though it doesn’t beat big planes, switching to point-to-point travel might lower total travel emissions.

The 1970’s were also considered the golden age of plane hijackings.

Or at the very least, there should be flight options without luggage.

And with rising baggage fees, it might even save money.

Of course, trans-ocean flights might still need to carry luggage, but it still might be more efficient to send via cargo plane.

The most common passenger plane in the US.

Eli Dourado made this point a while ago, but I can’t find his original tweet.

The continential U.S. is 3 million square miles. We can partition this into 300 patches of 100 miles on a side (10,000 square miles). A plane flying from the center of one of these patches would need 200 miles of range to reach neighboring airports.

There are a lot of opportunities to improve eVTOL flight. Magpie Aviation has a clever idea to tow planes by cycling in several electric planes each flight. Wireless power transfer could also come in handy. Hydrogen aerostats could be used to boost eVTOL’s to their desired altitude.

This is essentially a Georgist tax on possession of airport slots.

This goes against my anti-regulation instincts, but it’s worth considering for the opportunity to make in-flight amenities much better.

With one pilot in the cockpit, does that give one person too much power? What if they decide to hijack the plane? The number of such incidents is extremely low, but regardless, it would be easy to establish some sort of override where the copilot on the ground can take control of the plane under extreme circumstances.

Like with removing luggage, we can catalyze this transition by offering separate flights with lower prices to assess demand.

It’s unclear how much this would increase total pilot hours, pilots today are already using stimulants (e.g. caffeine) to some degree.

Methane-based engines could usher in a new paradigm of fighter jets all on their own. An unmanned craft with a blended wing body and electric turboprops to power the onboard compute and radar, all cooled with cryogenic methane. The higher energy density gives a boost to super- or hypersonic designs based on ramjets or rotating detonation engines. Main drawback is the new military logistics required. You would need new aerial refueling planes for LNG and new oilers, though aircraft carriers could potentially get away with reforming fuel into methane.

I think the 0 luggage is a bit more dubious of an idea.

Firstly, some people decide to fly at the last minute. So the "pack ahead of time" is problematic if you aren't planing ahead.

What might be in the luggage? A laptop. Cloths. Toothbrush. Miscellaneous personal items. These are items that people use frequently, and may not have a spare of. "I'm going on a flight next week, so I need a second toothbrush, one to pack and one to use until then". That is the sort of inconvenience that adds up across many small items.

Then the luggage needs to be delivered. So you need to deliver it to an airport, and have the some airport baggage collection mess. (Or you could have it delivered to your destination, and get a whole lot of new problems)

You would need to take the extra bag into the nearest post office at least.

If your travel plans are more complicated, say with 4 flights spread over 2 weeks, then your going to end up with several bags being delivered to several places in a confusing mess of logistics. And if you change your plans, and now the bag being delivered from A to B needs to end up at C, then woe betide you.