Tackle poverty, not inequality

Focusing on inequality statistics blinds us from actually helping people.

A rich man and a poor man stand in front of you. Floating above them is a dial indicating the Gini coefficient. You hand the poor man a delicious apple and the Gini coefficient goes down. You hand the rich man rich man a delicious apple and the Gini coefficient goes up. Both are good deeds, but the Gini coefficient makes it look like giving to the rich man is a bad thing. It’s not the most altruistic option, but it’s still good.

Next, being the puppet of my thought experiment, you smash the rich man’s car. The Gini coefficient goes down. It’s bad to destroy stuff, but just looking at Gini suggests you did a good deed1. The solution is to throw Gini out as a measure of goodness.

The reasonable way to make these decisions is to consider the well-being of each person, prioritizing the needs of the poor. When you do that, fighting inequality becomes an afterthought; growth-oriented policy and targeted redistribution do a better job of helping everyone.

Beneficial inequality reduction is rare

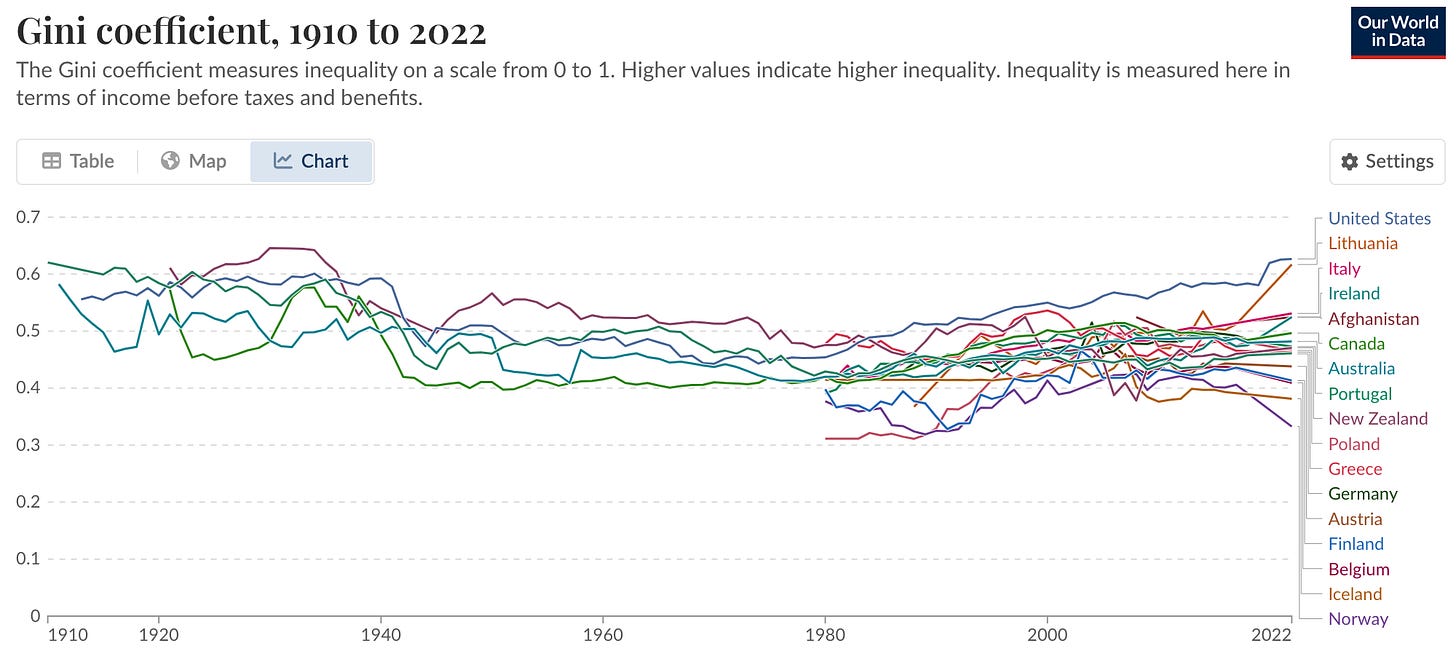

Historically, declining inequality coincided with terrible events like wars or pandemics. Improving material conditions coincided with increased inequality.

Looking across countries today, there are few admirable examples of high prosperity and low inequality. Nordic countries are renowned for their wealth and relatively-low inequality, but Income Equality in The Nordic Countries: Myths, Facts, and Lessons finds that:

“income equality in the Nordics is primarily driven by a significant compression of hourly wages, reducing the returns to labor market skills and education. This appears to be achieved through a wage bargaining system characterized by strong coordination both within and across industries.”

The Nordics achieved lower inequality by hampering growth. As I’ll argue in the next section, that’s a bad trade.

It’s also not clear that a place like the U.S. can imitate the Nordics without stagnation. U.S. redistribution is more generous than any European country, yet it has higher inequality2.

Zooming out, substantially lowering inequality in a developed country is without precedent. Across the tumult of the last century, Gini coefficients have barely budged3.

Growth takes priority

Economic growth and inequality are occasionally at odds. But if you care about people’s welfare, growth has to be the priority. Economic growth is the reason billions of people have left poverty. There is only one poverty strategy, nothing else comes close.

Redistribution depends wholly on growth to function. You need surplus via growth to have something to give to charity. Back when everyone was dirt poor, redistribution would merely move dirt around. As Maxwell Tabarrok points out, “[i]f you divvied up global GDP today equally across all 8 billion people, everyone would be well below the US poverty line.” No amount of redistribution today will save us.

Material wealth comes from our capacity to serve people’s needs at scale via commerce. Pushing piles of paper around does nothing to change that capacity. We have to grow until we’re productive enough to provide for everyone.

We can’t declare victory once aggregate wealth is high enough, because much of it will be in the hands of the rich. Nor can we simply distribute all the money and be done with it. Global productive capacity would collapse, and the paper we redistributed would be worthless, a huge setback.

We have to redistribute the right way, taking care to keep the system of commerce in place. The obvious ways to tax the rich would backfire. Poorly designed taxes reduce innovation. Inheritance taxes redistribute very little. Wealth taxes are more damaging than other progressive tax systems.

Instead, a system of redistribution must work hand-in-hand with commerce, ensuring that productive capacity is maintained now and in the future. Better yet, let’s build a system of redistribution that reinforces growth. Many forms of redistribution can be justified on an economic the basis. For instance, eliminating a poverty trap makes people more productive, which benefits everyone. And social insurance systems prevent people from entering a poverty trap in the first place.

Growth can lower inequality in some cases

So far, I’ve argued that reducing inequality is hard and that when inequality conflicts with growth, we should choose growth. Fortunately, there are some cases where growth reduces inequality.

Some of the most unequal nations on Earth have very low GDP. This is because of authoritarian policies that enrich the oligarchy while impoverishing everyone else. A commitment to market rights would both reduce inequality and increase growth.

Growth can also lower global inequality. Most of the world’s inequality exists between countries, not within them. Boosting growth in poor countries would close the gap. It also encourages voluntary redistribution. Charitable donations increase with wealth and stability4. The U.S. is one of the most generous countries both in terms of total spending and spending as a percent of GDP5.

The innovations that come with growth lower consumption inequality in some regards6. Bezos uses the same iPhone as you. There’s little difference in the quality of high-end vs. low-end cars in terms of measurable performance. Rich and poor are roughly equal in terms of calories consumed.

The broader trend is that productivity growth means you need fewer hours of labor to obtain the same goods. As marginal utility falls, the wealthy switch to high-quality goods rather than more low-quality goods. As everyone has more to spend, the difference between high-quality and low-quality falls, owing more to signaling than to measurable attributes7.

Conclusion: poverty is what matters

I don’t care how rich people get as long as we provide for the worst off. Because that’s what actually matters. Our yardsticks for inequality tell us that some people lack material wealth and that our society has the productive capacity to help them. So let’s help them. A clearheaded approach requires growth-oriented policies and redistribution systems that reinforce growth. Without these policies, we’ll all be equally poor.

Further reading

Lane Kenworthy’s forthcoming book Is inequality the problem? appears to make similar points.

Wealth and history: A reappraisal. “The new results influence our understanding of the long-run evolution of wealth. They question the view that unfettered capitalism generates extreme levels of capital accumulation.”

Beyond GDP? Welfare across Countries and Time. An alternative measure of economic welbeing that “ incorporates consumption, leisure, mortality, and inequality …”. The measure correlates strongly with GDP, but western Europe looks considerably better on this measure.

Has Consumption Inequality Increased With Income Inequality? Why the two aren’t the same, why consumption inequality is the only thing that matters, and a plea for more data on consumption.

The Wealth Inequality of Nations. Housing equity can explain cross-national differences in wealth inequality.

International Income Inequality. An illustration of the wealth inequality between India and the U.S.

The limitations of decentralized world redistribution: An optimal taxation approach. Models how much global inequality would change if redistribution was within-country vs. global. Within-country redistribution would have a minimal effect on global inequality.

David Splinter argues that “[t]he U.S. tax system is highly progressive.”

The (Un)Importance of Inheritance. Inheritance taxes would do little to reduce inequality.

You can’t tax a dead man. More on the point that moving money between bank accounts without changing productive capacity does less for the poor than you might think.

Was It Demography All Along? Population Dynamics and Economic Inequality. An aging population in developed countries has contributed to rising equality “… and coupled with demographic projections of an aging population and continued low fertility portends a broad trend toward greater equality over at least the next two decades.”

There is only one poverty strategy: (broad based) growth by Lant Pritchett.

Alleviating Global Poverty: Labor Mobility, Direct Assistance, and Economic Growth by Lant Pritchett.

On Redistribution by Paul Christiano.

Tax Cuts and Innovation. Poorly designed (redistributive) taxes harm innovation.

Flow-through effects of innovation through the ages. Historically, investing in innovation was vastly more impactful in the long run than saving lives.

In theory when including public goods provision, some degree of inequality is good: A Note on Pareto Improving Lotteries in Voluntary Public Good Provision.

Why Are Relatively Poor People Not More Supportive of Redistribution? Evidence from a Randomized Survey Experiment across Ten Countries. “… [P]eople who are told they are relatively poorer than they thought are less concerned about inequality and are not more supportive of redistribution.”

This last result makes it unclear if more informed voters or more a democratic redistribution system would redistribute more than today. By anchoring to current living conditions, people may choose an inadequate level of redistribution.

Not only is it bad to destroy stuff, but creating a precedent for destroying peoples stuff has all sorts of negative consequences that impoverish everyone, poor people included.

That’s partially because the U.S. is diverse and accepts a wide array of immigrants. Which is a good thing.

Eyeballing my previous results on income and utility, these within-country changes seem pretty small for overall utility.

Interestingly, the rich give a slightly larger share of their wealth to charity, implying that a more unequal world gives more to charity overall. Growth also has spillovers into finding good philanthropic ventures.

Though much of this can be attributed to the U.S.’s higher religiosity.

Innovation also creates new types of goods that are only accessible to the rich. But further innovation tends to diffuse these technologies to everyone. This process of first serving the rich and then serving everyone else is a key driver of innovation and prosperity.

In theory, taxing consumption on pure signalling goods can be a pure gain. In practice, it’s hard to determine what is signalling and what is not. Though a consumption tax can give us some of the benefit.