Capturing CO2 is sometimes touted as a way to reverse climate change. Who wouldn’t want to undo the damage we’ve done? But we shouldn’t assume that reversing climate change is a good thing.

For the purposes of this post, “reversing climate change” means using CO2 capture to draw down global CO2 concentrations. Potentially with the goal of reaching a preindustrial CO2 concentration.

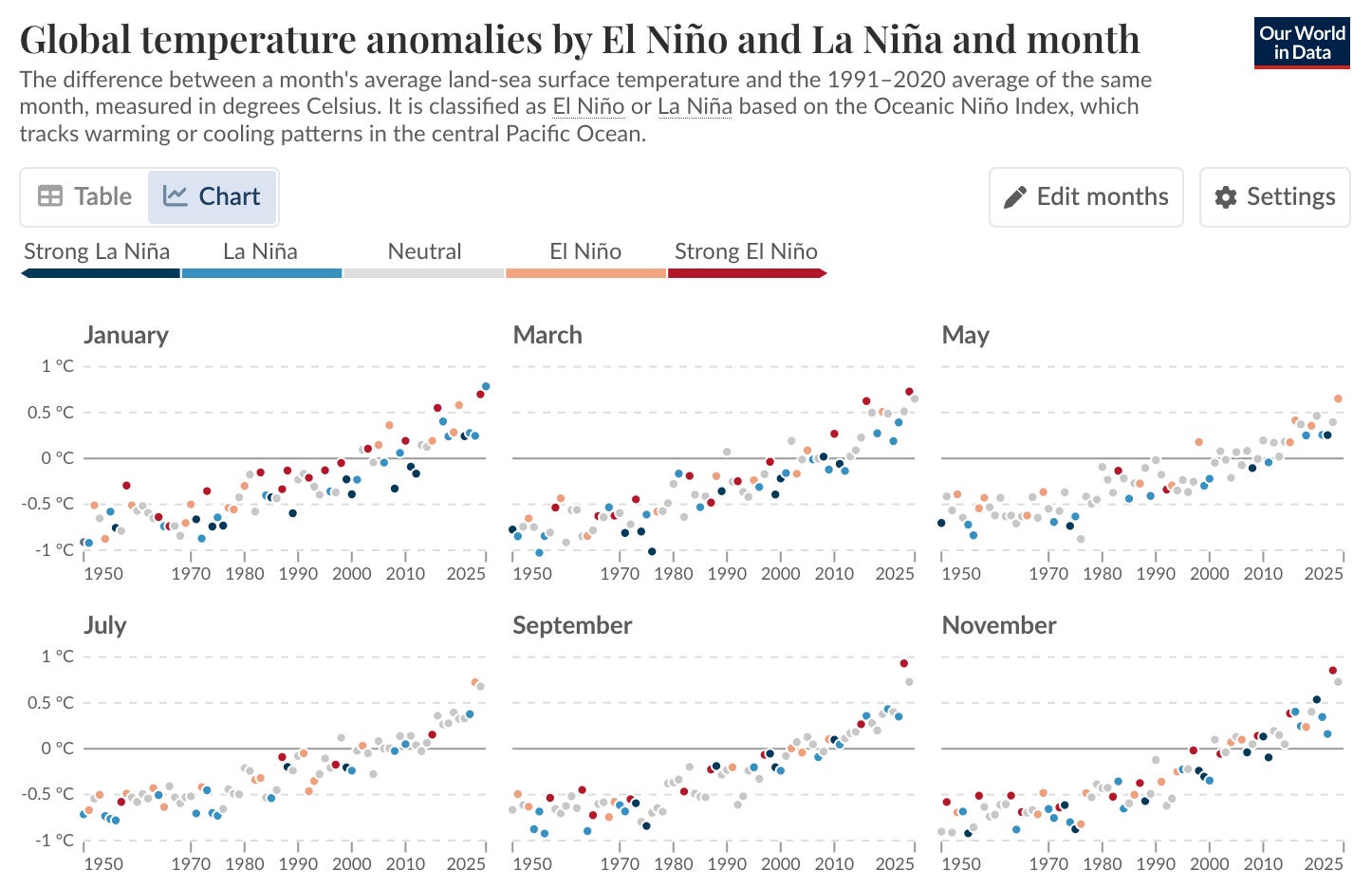

To put reversal into context, it’s helpful to consider what would happen to global temperatures on different emissions paths. If we continue to emit net CO2 at a steady rate, temperature will continue to rise. If we start drawing down CO2 at a steady rate, temperature will fall. What happens if we reach net zero? As I’ve covered before temperature will stay constant. In other words: stop emissions, stop warming. This is a surprising result that we have only recently found good evidence for. It turns out that natural climate sinks draw down sufficient CO2 to cancel any “momentum” from past emissions.

Reasonable people agree that emitting CO2 indefinitely is a bad idea. But there doesn’t seem to be much consensus on whether to draw down CO2 or simply hold at net zero. I think net zero is the right answer.

The first problem with reversing climate change is that it’s hugely expensive. Recapturing all the CO2 emitted in the last century or so takes orders of magnitude more effort than cancelling out current emissions.

Perhaps this price is worth paying to undo the ravages of climate change? Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that.

One problem with this line of thinking is that everything is more adapted to today than the preindustral climate. We’ve spent the better part of a century in a warmer-than-natural climate. All the people and wildlife alive today are much better suited to recent temperatures than historical temperatures. Returning to a preindustrial climate means repeating all the pains of adaptation for questionable benefit.

Instead of anchoring on a preindustrial climate that we have long since left, we should aim to minimize further adaptation costs. Since we are best adapted to the climate of today1, we should aim to pause climate change by reaching net zero as soon as reasonably possible.

From there, we can ask what the right temperature is for the global thermostat. It needs to be substantially warmer than preindustrial to avoid ice ages, cold deaths, and keep heating costs low as these are more significant problems than their compliments. But today’s temperatures produce too many heatwaves and reduce crop productivity. Eyeballing the charts below, perhaps the 0.5 C mark is a reasonable initial target2. Unfortunately we don’t yet have the tools to make a finer distinction.

Whatever temperature we select, there will be tradeoffs. The ideal climate for corals is different than the ideal climate for crops. It’s better stick to a certain climate and pursue keyhole solutions3 than to constantly fight over the thermostat or continually update our notion of the optimal temperature.

For these reasons, our near term goal should merely be to pause climate change. This pause can be achieved by reaching net zero.

Arguably we are better adapted to the climate of 5-10 years ago, implying a more limited drawdown.

In all of this, the global thermostat should change slowly as sharp changes cause additional damage.

For coral bleaching, it may be cheaper to employ local cooling techniques than to lower global temperatures.

Arguably the same technologies would be used to reach net zero as would be used to go carbon negative. Do you see a meaningful different in strategy based on pause vs reverse, or is it simply a matter of differences in degree (pun unintended) rather than kind?